|

I

have always been fascinated by those energetic people from northern

France, known to history as the Normans. In the space of

two centuries the duchy of Normandy stood as a prime mover in European

affairs, not only completing the conquest of England but

also stretching its arms out to southern Italy and Sicily. Even

after the duchy lost its autonomy and was absorbed into the Kingdom

of France-proper it still exerted great power and influence within

that realm. Many of these men were larger than life figures who

led lives even Hollywood could not imagine. Not only have I had

a life-long interest in the Normans themselves but I have also had

a particular fascination with their arms and equipment.

Who were these people and what made them such a significant force

upon the European stage? What equipment and techniques made them

so effective on the battlefield? Can their lethality really be

a result of superior technology or was it something more intangible

like national pride? Perhaps it was simple greed and ambition that

fueled the fires of conquest?

Here we will discuss the Normans and their history and I will outline

my own personal attempt to recreate the arms and equipment of a

Norman warrior of the 11th century. Perhaps in that

last respect this is just as much my story as it is theirs.

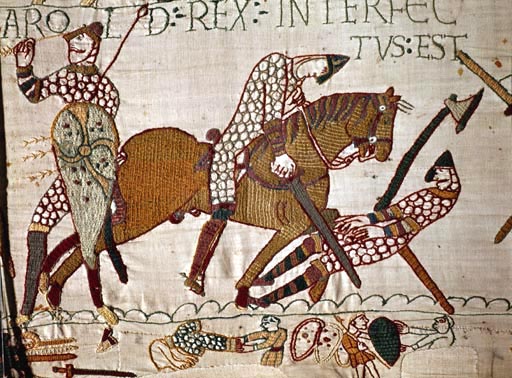

A

detail from the Bayeux Tapestry

A

detail from the Bayeux Tapestry |

Origin

As

the 10th century began Europe was at the height of the

so-called ‘Viking’ age. (The term ‘Viking’ being more illustrative

of their raiding activities than of the people themselves.) Seafaring

warriors from the Scandinavian countries of Norway, Denmark, and

Sweden had made incursions into northern Europe and the Slavic regions,

as well as penetrating as far as Asia minor and the North American

continent. In many areas these nordic raiders had ceased their

plundering and had become colonists and traders. In 911 a Danish

invasion fleet under the command of Hrolf the Ganger (‘Ganger’ meaning

walker as apparently Hrolf was rather tall and long-legged for the

age) sailed into the Seine Valley intent on stripping the region

of its worth.

At

this period in history France as we know it today did not exist.

The region was divided into duchies and counties that owed only

nominal allegiance to the French King Charles II, known as ‘the

Simple’.

Charles seems to have come to the conclusion that he could not deal

with the Danish invaders on a military level and decided to buy

them off. This had become a common practice in Europe when dealing

with ‘Viking’ invaders. However, instead of offering the Danes

gold or silver, (hence the term “Danegeld”.) Charles offered

them land instead. The land around Rouen was thereby ceded to Hrolf

and his army. This act can be seen as a rather pragmatic decision

by Charles since this area was already under Hrolf’s control and

the King had no effective means to dislodge the invaders.

In

912 Hrolf converted to Christianity and allowed himself to be baptized,

changing his name to Rollo in the process. Thus Rollo effectively

became the first Duke of Normandy (meaning “land of the northmen”.)

and by the time of his great-great-great grandson, Duke William,

the Normans had consolidated their rule over a large area that stretched

from the Cherbourg peninsula to the River Somme. Normandy retained

its autonomy until 1144 when it was invaded and taken by Count

Geoffery of Anjou. The duchy then became part of an Angevin

empire that lasted until 1204 when King Phillip used military force

to bring Normandy back into the French fold, along with Brittany,

Touraine, Anjou, Poitou, and Maine. For the first time in three

hundred years Normandy was again under Royal control.

The

Southern Empire

The

Normans are best known to history as the conquerors of England in

the year 1066. While this operation was certainly no mean achievement

it was far from the first example of Norman expansion and conquest.

Long before Duke William fell onto his face while disembarking on

the beach at Pevensey and cried, “I have the earth of England in

my hands!” the Normans were penetrating into southern Italy. (Sources

vary as to whether this statement was made by William himself or

another Norman knight in the invasion force.)

|

According

to the contemporary chronicler Amatus, in the year 999 a group of

approximately 40 Norman pilgrims were returning from Jerusalem and

were at Salerno when it was attacked by Saracen forces. Saracen

being the generic term used by Europeans for those of Islamic faith.

Apparently these ‘pilgrims’ were astonished and offended at the

lack of resistance by the local populace and obtained arms and horses

from Gaimar IV, the prince of Salerno. The Normans then succeeded

in driving away the attacking forces and were invited to remain

in Gaimar’s service. The travelers declined this offer and instead

returned to Normandy with an Italian envoy that was apparently quite

successful in recruiting volunteers “to come to this land that flows

with milk and honey and so many beautiful things.”

While there are various sources that give opposing dates for an

‘official’ start of Norman incursion into Italy this is the earliest

documented case of Norman involvement on the peninsula. Another

source, written by William of Apulia, speaks of a meeting in 1016

between Norman pilgrims and a disenfranchised Lombard noble by the

name of Melus. According to William this Melus had been involved

in an unsuccessful rebellion against the Byzantine Empire and was

now in exile. At this time most of southern Italy was under Byzantine

control and apparently Melus styled himself as something of a revolutionary.

In his account William states that Melus was successful in convincing

the pilgrims that the freedom of southern Italy could be achieved

with their help. It is unknown whether their willingness was due

to a sense of religious piety on the part of these Norman pilgrims

or simply a case of blatant opportunism. It must be observed that

the Normans were always ready and willing to combine religion and

opportunity if it was to their advantage.

Due

to the political nature of Norman society the oldest son of a house

would inherit all and younger sons were forced to depend upon their

own initiative, their choices usually being limited to military

service or a life with the church. Consequently, the envoy’s efforts

at recruitment were quite successful, with many younger sons making

the journey south along with those who had fallen out of favor with

the Norman Duke. Unlike the conquest of England the Italian enterprise

did not occur in piecemeal fashion. There was no single climatic

battle that decided everything like that which occurred at Hastings,

nor was there a quick follow-on campaign to consolidate rule. Over

the proceeding decades there was a steady flow of manpower towards

the Italian peninsula, and by 1046 the Normans had moved into southern

Italy in force. Sergio IV of Naples had granted them a “prime concession

of land”. This meant they were allowed to hold whatever land they

could retake from the invading Arabs of North Africa. These opportunistic

and energetic northerners were all too willing to take full advantage

of the situation. By 1053 the Normans had taken the entire southern

region of Italy, thereby creating a new empire. Unfortunately this

aggressive expansion had come to the notice of the current Pope,

Leo IX. It was indeed unfortunate for the Pope himself as he would

discover.

In

1035 members of one particular family entered the Italian scene.

This family, the Hautvilles, would become one of the greatest driving

forces of the Norman kingdom in Italy. Three of the younger Hautville

sons: William, Drogo and Humphrey arrived in Aversa to seek their

fortunes. The Hautvilles entered Gaimar’s service and in 1038 were

part of a 300-strong contingent of Norman knights sent to aid the

Greek Emperor of Constantinople, Michael IV, in an invasion of Moslem

Sicily. The expedition itself was without success but the Normans

in general, and the Hautvilles in particular, distinguished themselves

before leaving the campaign in disgust. William d’Hautville himself

was afterwards known as William Bras-de-Fer, or William of the Iron

Arm, due to his personal abilities. The Hautvilles would become

one of the primary forces in expanding the Norman holdings in Italy.

In 1046 another Hautville arrived who would become perhaps the

greatest member of the family and bend the very pillars of Christendom

to his will. This man was Robert Guiscard, known as “the Resourceful”,

“the Weasel”, or “the Wary” depending upon the source. Anna Comnena,

daughter of Alexus I of Constantinople, described the Guiscard in

the following manner:

This Robert was Norman by descent, of insignificant origin, in temper

tyrannical, in mind most cunning, brave in action, very clever in

attacking the wealth and substance of magnates, most obstinate in

achievement, for he did not allow any obstacle to prevent his executing

his desire.

|

Upon

his arrival Robert was disgruntled over not being given what he

felt was his proper due by his older brother Drogo. Instead of

being given a ‘proper’ fife his brother sent him south to Greek

Calabria, an area that had barely been penetrated by the Normans.

Whether Drogo expected his brother to expand their holdings, or

was simply intending to rid himself of a brother who was by all

accounts villainous and highly ambitious we will never know. Whatever

Drogo’s motivation may have been Robert Guiscard succeeded in taking

the region and established a base of power at San Marco Argentano.

From this location Robert steadily increased his holdings, and his

power, over the intervening years. In 1051 Count Drogo was assassinated

in his own chapel and was immediately succeeded by his brother Humphrey.

This change of command did little to change matters that had been

growing increasingly hostile for the Normans. The native Italian

populace had grown weary of the Norman’s strong-arm tactics and

it was now dangerous for even pilgrims to travel alone for fear

of attack.

Thus

it was that the new Pope, Leo IX, felt obliged to intervene and

in 1053 the Pope assembled a Papal army and allied himself with

Constantinople, with the intention of ridding Italy of this Norman

‘problem’. The Normans, under Count Richard of Aversa, Count Humphrey

d’Hautville and the wily Robert Guiscard, moved to intercept the

Papal army before it could combine with its Byzantine counterpart.

Contact was made on June 17th 1053 near the city of Civitate.

The Normans were rejected in negotiations and reluctantly engaged

the Papal forces. The Pope himself did not participate in the battle

but instead watched from the walls of the city as his army went

down to defeat. Civitate has been compared to the battle of Hastings

for its significance in the history of Norman Italy and in that

respect the comparison is appropriate. In a world-wide context

this comparison really doesn’t hold water since, unlike Hastings;

it had very little direct effect on the world outside of the region.

Still, many comparisons can be made with the elite of the Papal

infantry being defeated by Norman cavalry, just as the axe-wielding

Huscarls of Saxon fame saw defeat at Hastings. The Byzantine army

then withdrew without further hostility and the Normans held victory

in their hands.

The

Normans then exhibited the resourcefulness and opportunism for which

history has made them famous. According to William of Apulia, in

spite of the fact that they now held the religious leader of Christendom

as their virtual prisoner, they knelt before Leo IX and begged his

forgiveness. We will never know if this outward show of religious

submission was sincere or merely a medieval example of strong-arm

tactics covered by publicity spin and political correctness. Regardless

of the Norman motivation the result was Papal recognition of Norman

holdings in Italy. When Leo died the next year the new Pope, Gregory

VII, immediately allied the Papacy with the Normans at Melfi in

1059. In spite of Robert Guiscard being excommunicated by the Pope

no less than three times, the Normans thereafter retained Papal

approval in their activities. This association with the Papacy

would continue throughout the rest of the ‘Norman’ era and would

play a key role in the launching of the Crusades at the end of the

11th century.

Count

Humphrey had died in 1057 and was succeeded by Robert Guiscard,

first as regent and then as count. Apparently the hereditary rights

of Humphrey’s young son Abelard were of no consequence. Two years

later Robert also ascended to the position of duke of Apulia and

Calabria. In 1056, Roger, the eighth and youngest of the Hautville

brothers arrived in Italy. Robert immediately sent his younger

brother off to Calabria with a force of sixty knights. At the age

of 26 Roger d’Hautville would gain either experience or a grave

in southern Italy. The younger Hautville did indeed find success

and became his brothers most trusted lieutenant. In an era of dubious

family loyalties the two brothers remained steadfastly devoted to

each other throughout the remainder of their lives. Whether this

was due to any sense of familial loyalty or simply shared ambition

will have to be for the reader to decide.

After

two probing incursions the conquest of Sicily was undertaken in

1061. This operation would take thirty years to complete and was

possible due to the divisions present between the Moslem factions

inhabiting the island. The Normans continued to face problems within

the already conquered areas of Italy, as well as a chronic shortage

of manpower. When these factors are combined with very stiff Moslem

resistance upon Sicily itself the duration of the conquest isn’t

surprising. Out of necessity the invasion of Sicily was an amphibious

operation with men and horses traveling by ship to an area south

of Messina. The significance of this enterprise cannot be overemphasized.

A few years later a similar, though much larger, operation would

be undertaken by Duke William of Normandy during the invasion of

England. Therefore, it would be logical to assume the lessons learned

during the invasion of Sicily were put to good use in 1066.

The

first landing south of Messina took place at night with a fleet

of thirteen ships. An original force of 270 knights under the command

of Roger d’Hautville was joined the next day by a further reinforcement

of 170 knights. This force of less than 500 then took the city

of Messina before Robert Guiscard had made landfall. Over the next

thirty years the Normans would expand their domination of Sicily

through a series of successful campaigns, including the decisive

defeat of a much larger army under the command of Ibn al-Hawas.

Contemporary sources list the Norman numbers at 700 with an opposing

Saracen force of 15,000. Of course these contemporary sources must

always be taken with a grain of salt when it comes to hard statistics.

This battle was the first significant contact between Norman and

Saracen forces and is interesting for this reason alone. Many historians

have credited the initial European success during the crusades to

two factors. The first, political disunity among the Moslem population

is a logical and quite probable contributing factor. The second,

unfamiliarity with European military tactics, seems less valid.

This first contact between Norman and Saracen forces occurred over

thirty years before the first crusade began. Consequently, it is

logical to assume that the opposing sides were quite familiar with

each other’s tactics by 1096. After the fall of Palermo in 1072

Robert Guiscard never returned to Sicily but instead concentrated

on matters pertaining to mainland Italy. The rest of the Sicily

campaign was left in the hands of his brother Roger. The city of

Noto finally fell in 1091 and marked the completion of the Norman

conquest of the island.

During the campaign the Normans made heavy use of sea power to transport

invasion forces as well as laying siege to cities like Syracuse

and Palermo. The ability of the Normans to use of these unfamiliar

modes of transport and attack can be seen as evidence of their willingness

to adapt to the circumstances at hand. It was also during the

conquest of Italy and Sicily that the concept of a Holy War against

the Moslem world began to take shape in the Norman mindset. So

when Pope Urban II first preached of a holy crusade on November

27th 1096 the idea was far from unknown. By the end

of the 11th century the entire southern half of Italy,

as well as the Isle of Sicily, was under the domination of the Norman

adventurers. Other famous names would follow such as Bohemond of

Taranto, a son of the Guiscard himself who was apparently as cunning

and ruthless as his father. Bohemond would become a key figure

during the first crusade and would rise to fame on his own abilities

instead of resting in the shadow of his father. When Robert Guiscard

died of typhoid on July 17th 1085 he was buried alongside

his brothers in the abbey of the Trinity at Venosa. His tomb was

inscribed with an epitaph that could, perhaps be fitting for the

entire Norman experience of the 11th century:

‘Hic terror mundi Guiscardus’

“Here lies Guiscard, terror of the world”.

Robert’s nephew, Roger II, would succeed his father and uncle by

being crowned king at Palermo in 1130. Roger II then ruled over

a Norman kingdom that would endure until the death of King Tancred

in 1194. The southern kingdom the Normans had so miraculously created

was then absorbed into the Hohenstaufen Empire of Henry VI.

What

reasons can we find for the Norman success in Italy? The Italian

campaign was not a heavily supported European enterprise, nor was

it an example of overwhelming an enemy with superior force. The

mercenaries, who would later become dukes and barons, were the lesser

sons of Norman nobility. In many cases they were adventurers and

exiles who could hope to receive little assistance from their homeland.

One contributing factor is undoubtedly the Norman’s military expertise.

It is a bit of a stretch to claim that the Normans were the originators

of the use of heavy cavalry in the European context. However, they

undoubtedly perfected the concept and made the most of it. While

the Norman pedites, or infantry, surely played their part

it is the milites, or knightly cavalry, that are spoken of

in the contemporary chronicles. Time and again we read of heavily

outnumbered Norman cavalry smashing a superior enemy force. While

this may very well be propaganda we must remember that not all who

wrote of these exploits were pro-Norman. We must also remember

that Norman cavalry could, and often did, dismount to fight as infantry

when the situation demanded it.

|

This

tactical sense of flexibility was surely a strong weapon in the

Norman arsenal. Nor should we underestimate the psychological factors

when we speak of Norman success. These descendants of Viking raiders

had cast off the pagan religions of their forefathers and had embraced

Christianity. However, medieval Christianity was a far different

thing than it is here at the dawn of the 21st century.

To the medieval mind God moved and worked in all things in a very

absolute sense. If the Normans gained success through military

conquest it was simply God’s will that they should do so and if

they received Papal blessing for it then so much the better. The

fact of that blessing being won at the point of a sword was of little

consequence to the Norman mind. Combine this sense of religious

righteousness with a willingness to bend that same religion, and

secular law, to fit their own needs and you have a very dangerous

combination when combined with skill at arms.

Still,

the Normans were not above sensing the reality their situation and

molding it to fit their needs. The Moslem inhabitants of southern

Italy and Sicily did not endure the wholesale rapine and slaughter

that would occur during the first crusade. The Normans shaped the

local forms of government with their own brand of feudalism, yet

the local non-Christian populace was allowed to remain in positions

of influence in trade and commerce.

The modern mind may look upon these events of nearly a millennium

past and view them as a form of enlightened tolerance. In my opinion

this would be a mistake. The Normans knew they were sleeping among

the enemy and if they were to succeed the local inhabitance would

need to be placated, and brought into the fold as much as possible.

They simply did not have the manpower to rule with an iron fist

that was completely closed. Instead they were forced to change

the circumstances to their advantage, a skill they honed to a razor’s

edge. Even though they faced unrest and rebellion on one scale

or another during the entire time of the southern kingdom’s existence,

it is a remarkable testament to their drive and skill that the Normans

were able to rule effectively with so few numbers. The Norman domination

of the Siculo-Italian region also produced a type of architecture

that combined elements of northern European, Greek and Moslem design

into a unique style. Many of the architectural works that still

exist in Italy today are seen as classic examples of Norman achievement.

In the end all that can firmly be said is that a relatively small

group of northern mercenaries achieved improbable success and carved

out an empire by shear tenacity and force of will. By helping to

develop the crusading mindset, this kingdom would be partially responsible

for moving the Christian and Moslem worlds onto a course that would

consume them for the next two centuries.

The

Conquest of England

|

By

now it should be obvious there is much more to the Norman people

and their history than the invasion of England. Nevertheless it

is this singular event for which they are best remembered. If the

common layman is asked about his knowledge of the subject he will

generally comment on Duke William the ‘Bastard’ and his conquest

of England. It is a pity that the common perception of such an

energetic people is usually distilled down to this one event. Still,

it must be admitted that, while this one event should not define

the Normans, it is arguably their most significant contribution

to world history in general and the geopolitical climate of the

middle-ages in particular. Not only is the conquest of England

itself significant but the battle of Hastings is also equally worthy

of study. Very few battles of the medieval period were as long

and hard-fought, or as decisive, as the one that occurred on a ridge

some seven miles north of Hastings on October 14th 1066.

To fully understand this battle, the proceeding conquest of England

and their importance to world history, it is necessary to examine

the events leading up to them.

During

the latter half of the 9th century English kings tenuously

held onto the realm created by their predecessor Alfred ‘the Great’.

Alfred had gained a foothold in Wessex and from there his successors

continued attempts at driving back their Nordic adversaries. Despite

these successes the country was still plagued by attacks from Nordic

invaders and would-be colonists. These attacks would continue throughout

the later 10th century and into the first decades of

the 11th. Due to this unending pressure the rule of

AEthelred II, known as the ‘Unraed’ or ‘Bad Council’ (later corrupted

to mean ‘Unready’), was reduced to a state of irrelevancy. Fearing

the worst AEthelred sent his two sons, Edward and Alfred, to live

in the relative safety of the Norman duchy.

Then, after more than two decades of combat, AEthelred’s reign came

to an end and he was deposed by the Danish-born King Cnut in 1016.

Edward and Alfred were then raised in the Norman court and this

twist of fate would prove to have far reaching consequences for

the English people. When Cnut died in 1035 his two sons, Harold

Harefoot and Harthacnut, quarreled over the royal succession. Both

would rule briefly: Harold Harefoot from 1037 to 1040 and Harthacnut

from 1040 to 1042. During the reign of Harold Harefoot tensions

were further heightened by the arrival of an invasion fleet under

the command of Edward and Alfred. Duke Robert of Normandy had shown

support for the Saxon brothers by supplying them with a fleet of

approximately forty ships.

Edward landed on the south coast and fought a battle at Southampton

but later withdrew back to Normandy due to insufficient manpower.

The unfortunate Alfred faired far worse than his brother. He landed

at Kent and was captured by Earl Godwin of Wessex. The Wessex had

grown rich and powerful under King Cnut and was all too eager to

turn the Saxon exile over to the then-reigning Harold. Alfred was

tortured and later died from the depredations committed upon him.

These events would lay the seeds of a deep and abiding hatred of

Earl Godwin within Edward’s heart. At this point none of the period

chroniclers speak of any kind of widespread support for Edward among

the Saxon people. Consequently, a succession to the English throne

must have seemed like nothing more than a dream to Edward. Future

events would prove otherwise.

By

1042 Cnut’s sons were dead and Edward found himself in a position

that was both surprising and perhaps a bit unenviable. With Cnut’s

line extinguished Edward was now offered the English crown. Even

though he was now poised to assume the throne of England by all

accounts he knew little of the country or its people. We will

never be certain but one can’t help thinking he accepted the crown

with a bit of trepidation. Edward had spent most of his adult life

as an exile in Normandy and was probably more Norman at heart than

Saxon. He knew little of the great Earls who controlled England

or the unique political structure of the countries government.

In many ways men like the hated Earl Godwin were the real power

in Saxon England. Godwin’s income and holdings were nearly equal

to that of the king himself and he was a man of great influence.

Such was the make-up of the Saxon system of government that the

King did not rule with complete autonomy but instead depended upon

the support, and to a certain extent the approval, of powerful Earls

like Godwin of Wessex, Leofric of Mercia and Siward of Northumbria.

Edward did attempt to rid himself of the Godwin family in 1051 when

he sent them into exile. However, the Godwins returned the following

year, armed and with a strong support cell. Due to a legitimate

fear of civil war Edward backed down. From this point forward the

king’s power was terminally weakened. By all accounts this power

struggle between the King and Earl Godwin continued until the Earl’s

death in 1053, when the Earldom was assumed by his eldest surviving

son Harold. Godwin’s power was great enough that in 1045 he had

manipulated King Edward into marrying his daughter Edith. This

was an obvious way to ensure the passing of the royal succession

to the Godwin family. However, throughout the proceeding years it

would become obvious that the marriage would prove to be fruitless.

By all accounts Edward was a pious man more concerned with his God

and religion than most other things. We shall never know whether

the barren union was a result of the king’s disinterest, or came

from a desire to deprive the Godwin’s of what they wanted most.

Regardless of Edward’s motivation, his lack of providing a successor

would give the Godwin family its opportunity later in 1066.

|

Upon

ascending the throne Edward appointed several of his Norman friends

to key positions throughout the realm. According to the Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle many of these men were highly unpopular with Edward’s

subjects. One of these men, Robert of Jumieges, was named bishop

of London in 1046 and later elevated to archbishop in 1051. Robert

was then required to travel to Rome to receive Papal approval of

his holding of the see of Canterbury. If we are to believe the

contemporary Norman chronicler William of Jumieges, the archbishop

then stopped in Normandy to offer Duke William the position as Edward’s

heir. William, a distant cousin, had been a boy during Edward’s

exile and Norman chroniclers tell us this offer was made as an expression

of gratitude towards his Norman friends. Saxon sources are silent

on this point and tell us nothing. This was not the only instance

where Edward dangled the carrot of the English crown before a likely

subject, so we will never know how serious his motives were. The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that Duke William traveled

to England that same year and contemporary Norman historians would

have us believe this trip was made to confirm acceptance of Edward’s

offer, but this remains unconfirmed. After Edward’s death on January

5th 1066 it was this supposed offer that was used as

justification for the Norman invasion of England.

Another

event which adds further mystery to the issue of succession is a

journey made to the continent by Harold Godwinson in 1064 or 1065.

French sources such as the Carmen de Hastingae Proelio, possibly

written by Bishop Guy of Amiens, state quite clearly that

the purpose of this visit was to confirm Edward’s wish that William

succeed him. On the other hand English sources like the History

of Recent Events in England, written by an English monk named

Eadmer some fifty years after the battle, tell a very different

tale. According to Eadmer, Harold Godwinson had traveled to the

continent with the express intention of securing the release of

his brother Wulfnoth and one cousin Hakon. Eadmer tells us these

two members of the Godwin family had been held as hostages at the

Norman court since 1052. It seems unlikely that Harold would have

subjected himself to such risk for two relatives who had already

been in Norman custody for at least twelve years and the truth will

never be known. Regardless of his original motivation for the journey

what is known is that, while enroute to Normandy, Harold’s ship

was blown ashore and he was captured by Count Guy of Ponthieu.

Ponthieu had a long standing custom of taking captives in this fashion

and a wealthy high-standing noble like Earl Harold Godwinson would

have provided quite a windfall. If contemporary sources such as

the Bayeux Tapestry are to be believed Duke William learned

of this situation and dispatched Norman emissaries to secure the

Earl’s release. The Bayeux Tapestry then shows Harold receiving

arms from William, possibly as an indication of Harold paying homage

to the Duke. The Tapestry goes further to illustrate Harold participating

in a campaign to quell rebels in Brittany and finally swearing an

oath of fealty on holy relics. Like most period sources the Bayeux

Tapestry is strongly one-sided in its depiction of the events.

Most sources are violently pro-Norman or pro-Saxon with very little

middle ground. What does seem certain is that Earl Harold Godwinson,

one of the most powerful men in England, and Duke William of Normandy,

a man perhaps more powerful than the king of France himself, knew

each other with something more than passing familiarity before that

fateful day in October of 1066.

We

could continue on with the complicated, and fascinating, story of

Anglo-Saxon England in the later half of the 11th century

but that is for a different time. This story concerns the Norman

people and our tale has now brought us to the most well-known one

of them all: Duke William of Normandy. William was born in 1028

as the illegitimate son of Duke Robert the Magnificent and Herleve,

a local tanner’s daughter. In 1035 Duke Robert died while on pilgrimage

and the young William assumed his place. Throughout the proceeding

years he would survive several assassination attempts and would

grow into a man who was as cunning as he was ruthless. It is because

of his base-born status that William was known as ‘the Bastard’

to his contemporaries. While illegitimacy was common, and did not

carry the stigma that it would in later centuries, this nick-name

was surely not a sign of affection by his fellow Normans. William’s

feelings on the matter were evident while attacking Alencon in 1051.

The defenders insulted the Norman duke by beating tanned hides in

reference to his base birth. After the town was taken the offending

parties were tortured and mutilated. By the time he sailed for

England in 1066 William was an experienced military leader, having

achieved his first victory at Val-es-Dunes in 1047 when he assisted

his nominal overlord, the French king, in suppressing a Norman uprising.

William achieved further victories over Geoffrey Martel, the Count

of Anjou, at Mortemer in 1054 and again against the French King

himself at Varaville in 1057, after the King had turned against

him. In 1066, at age 38, Duke William of Normandy was an experienced

and intractable military commander with an iron will.

|

The

validity of William's claim to the English throne has been hotly

debated and undoubtedly this trend will continue until the end of

time. Earl Harold Godwinson assumed the English throne on the 6th

of June, the day after Edward the Confessor’s death. This ascension

was not automatic. Even though Harold claimed that he had been

named as the old king’s successor, his appointment still required

the approval of the Anglo-Saxon Witan or ‘Great Council’.

This seems to have been readily granted as strong anti-Norman sentiments

had taken hold since the Godwin’s return from exile.

However, according to the Life of Bishop Wulfstan II written

by William of Malmesbury in the 12th century, Harold

was forced to make a trip to Northumbria because they would not

accept him as king. Together with Wulfstan he was able to overcome

the Northumbrian bias towards what they saw as southern decadence.

One can’t help but wonder if William was overly surprised by this

turn of events. Can we see his taking Harold on campaign in Brittany

as a way to familiarize him with a potential enemy’s military abilities,

fully realizing that they would one day meet in battle? Can the

oath-swearing on holy relics be seen as a way to further strengthen

his own claim while attempting to neutralize an opponent’s? This

line of thinking may cause us to read too much into these events

of so long ago. However, when we take into account the political

savvy for which the Normans as a whole were known, and William’s

keen grasp of military affairs, it doesn’t seem too far outside

the realm of possibility.

The

Saxon army that met the invading Normans on that October morning

in 1066 was a well established unified force backed by the complex

governmental system of a wealthy nation. In contrast the Norman

army was something of a cosmopolitan affair. By the time of the

invasion Duke William had already won a well deserved reputation

as a keen and successful military leader. Because of his success

he was able to attract men not only from his subjects in Normandy

and Maine but also from Aquitaine, Brittany and possibly the Norman

kingdom in southern Italy. Most scholars view this later inclusion

as a strong possibility rather than a definite fact, but if men

from the Siculo-Italian region did indeed take part in the invasion

their experience with amphibious operations would have been invaluable

to their northern brethren. The Bretons themselves were all too

eager to take part in the conquest of England. Their ancestors

had settled in Brittany after having fled the Island during the

Saxon conquest of centuries past. There can be little doubt the

Bretons saw the operation as not only an opportunity for profit

but also revenge. Upon learning of Harold’s perceived treachery

William also appealed to Pope Alexander II for the one thing the

Normans never wanted to go into battle without: the Papal blessing.

The blessing was granted and a banner given to William by the Pope

accompanied the Norman army. Oderic Vitalis describes it as ‘the

banner of St. Peter the Apostle’ but the exact form is unknown.

Nevertheless, the Normans sailed for England with the all too familiar

confidence that they were doing the work of God.

The

size of the Norman fleet, and the army it carried, has been widely

debated by scholars. William of Jumieges tells us that the fleet

numbered 3000 ships, while the 12th century chronicler

Wace gives a much lower number of 696. A 12th century

document known as the Ship List of William the Conqueror,

apparently written between 1130-1160 and believed to be a copy of

an older document possibly written as early as 1067, gives us a

detailed list of the ships supplied to the invasion force by Duke

William’s vassals. Men such as the Duke’s half-brothers Robert

of Mortain and Bishop Odo of Bayeux, William FitzOzbern and the

bishop of Le Mans are mentioned as owing a specific number of ships.

The list sets the total owed by William’s subjects at 1000 and when

we consider the possibility that the Duke’s other allies supplied

their own ships it can be seen that the fleet was, in all probability,

fairly large. Likewise, the size of the Norman army will also never

be known with any degree of certainty. William of Poitiers puts

William’s army at 60,000 men. Most modern historians have discounted

such large numbers and generally agree upon a figure of somewhere

around 7000 men. This is based upon the dubious premise that medieval

armies were invariably small. Whatever these numbers of ships and

men may have been there is one thing we can be sure of: Duke William

of Normandy was an astute military commander with a successful history.

He knew his opponent and the resources available to him. As William

does not seem to have been a man prone to rash and impetuous action

we can assume that he assembled a force large enough to have some

assurance of success. The fact that he was able to assemble a large

invasion force, and hold it together in encampment for an extended

period of time, is a testament to his dynamic leadership qualities

and organizational skills.

The

Norman fleet then waited for favorable winds and finally departed

in early evening from St. Valery on the 27th or 28th

of September. William’s personal ship, the Mora, was the

largest in the fleet and a gift from his wife Mathilda. Apparently

the Mora was faster than the rest of the fleet and she soon

left them over the horizon. At dawn the duke realized they had

left the fleet behind. When the men with him began to despair he

calmly ordered the ship to drop anchor and wait. He then sat down

to a leisurely meal, outwardly unperturbed at the course of events.

As soon as the rest of the fleet came into sight the anchor was

raised and the course of history was set. At some time before 9:00am

the fleet sighted Pevensey bay and made landfall within the lagoon.

The Normans then commenced disembarking and immediately began to

fortify the old Roman fort located there. As Duke William stepped

ashore he fell onto his hands and knees on the shale beach. This

would have been considered a bad omen by his comrades. Fortunately

either a nearby knight or the duke himself made the aforementioned

utterance about him having England in his hands and the situation

was diffused. When no serviceable road was found leading eastward

from Pevensey the decision was made to move the army to Hastings,

with the disembarked troops transiting around the lagoon and the

fleet following down the shoreline. Construction then began on

a timber motte and bailey castle that would serve as a base of operations.

|

The

news of the Norman landing could not have come at a worse time for

King Harold and the Saxon army. All through the late summer he

had kept the fyrd on active duty along the southern coast of England

watching for the invasion he knew would surely come. He had lived

and fought with this iron-willed Norman duke and knew he was not

a man to be denied. Harold held his army together as long as possible

before finally releasing them for the needed fall harvest. When

an invasion finally came it was not from the south but rather from

the north. The Norwegian King Harald Hardrada had decided to force

his claim on the English throne and had set sail with an invasion

fleet of between 300 and 500 ships. Along with additional ships

commanded by Harold’s brother Tostig, they harried the northern

coast of England, finally landing at York. On the 20th

of September, at Fulford, The invaders clashed with a northern contingent

of the Saxon army under the command of Earls Morcar and Edwin.

The Norwegians gained the upper hand and the Saxons were defeated.

Little has been written on this battle but most historians put troop

numbers at between 5000 and 6000 on both sides, and casualties were

assuredly heavy for both armies. The invaders then set about consolidating

their position and further ravaging the countryside. On the 8th

of September King Harold learned of the Norwegian landing and immediately

sent out a recall. Less than two weeks later, with whatever troops

he had mustered, the Saxon king set out northward on an epic forced-march.

The morning of the 25th of September saw the Saxon army

marching from York along the road to Stamford Bridge where the Norwegian

army was encamped. Apparently the Nordic invaders were casually

basking in the morning sun and enjoying their good fortune when

the Saxons took them by surprise. The first hint of their doom

came from the glint of weapons within a dusty cloud on the York

road. Hardrada quickly organized his army and battle was joined.

The invading army was decimated by the Saxons, with Hardrada and

Tostig among the casualties. The survivors were allowed to retreat

to York where they departed for home in less than 30 ships. Much

could be written about the battle of Stamford Bridge. In many ways

it is as significant as the later battle of Hastings and just as

dramatic. The tale is full of dramatic dialogue between the key

figures and heroic actions by individual warriors, as well as the

treachery of King Harold’s brother, Earl Tostig. However, this

battle is not our primary concern here and must be left for a future

tale. King Harold must have been quite pleased at that point.

He had decisively defeated an invading army in the defense of his

realm as well as finally dealing with his troublesome brother, so

much for the Northumbrian hesitation at an overly soft king from

the south. However, his elation was to be short-lived and on the

1st of October a messenger brought word of the Norman

invasion in the south.

Upon

hearing the news Harold mustered his forces and repeated his epic

forced-march, this time southward, and reached London within five

days. Here he waited for fresh troops to be gathered before proceeding

south towards Hastings. William himself had done something unusual

for an invading army: instead of advancing inland he had consolidated

his camps at Pevensey and Hastings while waiting for Harold to come

to him. Perhaps William was concerned about overstretching his

lines of supply or being taken from ambush in the English countryside?

He also knew the timeframe for holding his army in position was

short as supplies were limited. Was William trying to provoke Harold

into an engagement by harrying the Sussex countryside? He knew

the area around Hastings lay within the Godwin holdings and that

Harold might see these actions as a personal affront. William was

aware of the English King’s capabilities from the campaign in Brittany

and as the previous battle at Stamford Bridge shows, Harold was

capable of quick action. Most of the duke’s victories before and

after Hastings were possible because of cold calculated planning

on the part of the Norman lord. He does not seem to have been a

man adverse to taking chances as the invasion of England itself

proves. However, if chances were to be taken it seems that William

tried to minimize them as much as possible, as would any good field

commander. What William needed was one decisive battle and he was

about to get it.

According

to the Carmen both leaders sent monks as envoys to parlay

with the enemy. These entreaties were rebuffed on both sides and

battle was now inevitable. King Harold moved his army out of London

and, according to the E text of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,

arrived on Caldbec Hill at a mustering point known as the Hoar Apple

Tree on the 13th of October. Here he was joined by further

contingents of the Saxon army. Both the Carmen and William

of Jumiegies tell us that Harold attempted to take the Normans by

surprise. William of Poitiers states the duke had sent most of

his men out foraging and fought before all of his men could be assembled,

that he took communion, hung the relics Harold had sworn his oath

upon around his neck and road to battle. In reality it is very

unlikely that William had most of his men out foraging when he knew

battle was likely. William of Poitiers is obviously a very pro-Norman

chronicler. As such he endeavored to elevate Duke William’s actions

as highly as possible. During Julius Caesar’s accounts of his invasions

of the island in 55 and 54 BC Roman foragers figure very prominently

in the action. Consequently, in his desire to portray the Norman

duke as a Caesar-like conqueror William of Poitiers may have used

this creative device to form a comparison. William of Jumieges’

more likely account states that William ordered his men to stand

by their weapons throughout the night and as dawn broke he mustered

them and marched north. Accounts of the battle itself are as widely

varied as they are uncertain. Some sources describe a battle of

tens of thousands taking place over a large area, while others describe

it as a relatively small affair confined to a ridge afterwards known

as Senlac. As with so many other things concerning Hastings these

details will never be known for certain. What is relatively certain

is that by the morning of October 14th 1066 the Saxon

army had occupied a ridgeline some seven miles north of Hastings

thereby cutting the north road to London and the Norman invaders

marched to meet them.

The

Saxon army fought in the time honored infantry shield-wall fashion.

The core of the army consisted of the Saxon noble’s household troops,

known as housecarls, with the balance filled out by the Saxon fyrd

or levy. While the housecarls were paid mercenary troops they showed

extreme loyalty to their lord. The Bayuex Tapestry shows

Harold’s personal guard fighting to the death over their fallen

lord while the common troops are retreating. The percentage of

these professional troops compared to the common fyrd soldiers is

unknown. The Bayeux Tapestry shows only a single archer

among the Saxon troops, so while they seem to have been present

their numbers are uncertain. Harold had disbanded the fyrd before

marching north to engage the Norwegians at Stamford Bridge. Afterwards

events proceeded rapidly enough that one has to wonder how much

time he had to reassemble the bulk of his army. Was the bulk of

the Saxon force comprised of the hard bitten mail-clad housecarls

or the less well equipped soldiers of the fyrd? We shall never

know. In contrast the Norman army consisted of three separate sections

of missile troops, infantry and cavalry. How well William could

exploit the greater versatility of his army would be limited by

the battlefield’s terrain. Some sources, both modern and contemporary,

are of the opinion the battleground was chosen by William, with

the Saxons being forced to battle before their army was fully assembled.

In my opinion this is incorrect. Harold Godwinson was himself an

experienced military commander with a long track record of success

throughout his ten years of campaigning against the Welsh. The

chosen battleground would seem to favor the Saxons more so than

the Normans. In front of a strong ridgeline the field sloped down

between the headwaters of two streams causing something of a bottle-neck

and while the thickly wooded nature of the area would hinder any

necessary retreat it would also prevent flanking attacks. Period

sources such as William of Malmesbury and the 12th century

Wace speak of ditches being dug and hidden by the Saxons. One section

of the Bayeux Tapestry would seem to corroborate them as

it shows Norman horsemen falling into a watery ditch apparently

lined with stakes. If these sources are accurate they would indicate

that Harold had occupied the ground first, with enough time to throw

up significant defensive works. From an offensive standpoint the

Saxons were in the stronger position.

William

seems to have had no choice other that to make a full frontal assault

on the Saxon position and the army attacked, with the French on

the left (Saxon left), the Bretons on the right and the duke with

his Norman followers in the center. Thus began one of the longest

and bloodiest battles of the medieval period. The Carmen dresses

up the battle’s opening with a tale of the juggler Tallifer juggling

swords before the Saxon army and then killing one of their men before

he was killed himself. Whether this event actually occurred or

whether it is merely dramatic elaboration by the Carmen’s

author is unknown. Guy of Amiens states that the duke ordered his

missile troops, primarily armed with crossbows, to proceed up the

ridge in the front rank. Guy tells us the duke had intended for

these archers to support the flanks of his cavalry, but due to the

terrain he was forced to use them in this fashion. While the Bayuex

Tapestry does not illustrate a significant number of archers

being present among the Saxons it does show hand-missiles, in the

form of axes and maces, being thrown throughout the battle. At

this stage in the battle we can imagine missiles of varying types

being launched by both sides in an attempt to soften up the enemy

ranks. Guy of Amiens further states that shields were no proof

against bolts from the crossbows. However, given the sloping terrain

it is uncertain just how effective these weapons were against the

Saxon shield wall. Eventually William withdrew his missile troops

and ordered his pedites, or heavy infantry, to attack. These

troops now clashed shield to shield in a straining contest of brute

strength. In the modern age we have become somewhat detached from

warfare by our technology, which often allows us to deal death and

destruction from hundreds of miles away. Not so in October of 1066.

The on-going combat would have been an intensely personal affair

with men glaring at each other over the rim of a shield, less than

an arm’s length away, with warriors trying to deal death with the

stroke of a Norman sword, or by cleaving an invader with the dreaded

two-handed axe. As little as a few miles distant the raging battle

would have gone unnoticed. But there on that ridgeline the crisp

morning air would have been filled with the curses of the enraged

and the screams of the dying, from men defending their country as

well as those seeking profit and conquest.

This

struggle probably continued for some time without advantage being

gained on either side, at which point Duke William would have chosen

to send in his cavalry, the armored Milites, to support the

infantry. The Bayeux Tapestry shows this cavalry as the

prime player on the Norman side of the equation. This is understandable

since the tapestry was evidently made for one of the victorious

Norman noblemen, supposedly Duke William’s half-brother Bishop Odo

of Bayeux. Whoever its owner was he was someone of note and would

have been among the mounted contingent of the invading army. In

order to please its owner the tapestry’s makers would have emphasized

this facet of the battle. However, it is highly probable that the

Norman cavalry did not play the all encompassing role portrayed

on the tapestry. The fact that the battle lasted so long may itself

be an indicator of this. Many battles between Saxons and Vikings

that occurred from the 9th century onwards were contests

of opposing shield wall formations, and many of these battles supposedly

went on for hours, far longer than many medieval battles. Chroniclers

tell us that the battle at Stamford Bridge itself lasted well into

the day. Perhaps the lengthy duration of the combat at Hastings

is an indicator of a major infantry engagement? When the cavalry

engaged in combat the terrain would not have allowed them to charge

en masse. They would have been forced to approach the Saxon shield

wall alone or in single-line formation. Period evidence like the

Bayuex Tapestry, as well as accounts by William of Poitiers

and others, tell us this is exactly the tactic employed. The tapestry

shows fully armored milites attacking the Saxon shield wall

with sword and spear, the latter being used in an over-handed fashion.

If the Normans had already developed the tactic of using a massed

cavalry charge with couched lances the terrain of the battlefield

prevented them from using it. The terrain also prevented William

from using his cavalry to flank the Saxon position. Consequently,

these mounted troops were denied much of their effective shock power.

Instead they were forced to approach their enemy from a much weaker

position, attacking the shield wall in-line with a frontal assault

of spear and sword, all the while trying to avoid being cut down

by the Saxon housecarl wielding his fearsome two-handed axe. The

Bayeux Tapestry shows this terrible weapon dealing death

to both man and horse, it was surely a feared and respected weapon.

This

shield to shield stalemate continued throughout the morning hours

with neither side gaining an advantage. Chroniclers then tell us

the Breton wing of the duke’s army began to crumble and retreat

due to heavy losses. As the Bretons retreated they were pursued

by contingents of the Saxon army. To make matters worse, word that

the duke had been killed now began to spread throughout the army.

Such was the importance of strong frontline leadership in medieval

warfare that a general retreat down the slope now began. William,

now in a precarious situation with a crumbling army and the enemy

on his flank, exercised the dynamic personality that had stood him

in good stead throughout his life. Raising his helmet to expose

his face, he rode among his men and assured them he still lived.

According to the Carmen at this point William rallied his

men and led them in another attack and the duke then killed King

Harold’s brother Gyrth, who had unhorsed the duke with a spear cast.

The Bayuex Tapestry shows this rallying of the troops, with

Count Eustace of Boulogne riding alongside the duke and shouting

to the men that the duke is well. The tapestry also shows Bishop

Odo rallying a group of horseman who had begun to retreat from the

battlefield. We don’t know how much active participation the duke’s

half-brother had in the fighting. In all probability he was present

mainly to add spiritual and emotional support to the venture and

saw little frontline action. William of Malmesbury speaks of a

group of Saxon warriors who had been cut off during this pursuit.

According to him they seized a hillock during the Norman counter-attack

and by using spears and rocks killed the pursuing horsemen to the

man. Wace also describes how many Norman horsemen broke through

the Saxon line only to be killed in a concealed ditch along with

many Englishmen. He then speaks of how more Normans died in this

ditch than at any other point in the battle. The Bayeux Tapestry

seems to corroborate the basic points of the event of the ditch

massacre in panel 52. This section of the tapestry shows the aforementioned

scene of Norman horsemen falling into a ditch lined with stakes

while Saxon infantry defend a small hill. Apparently William had

been able to avert disaster but only at a high cost.

Now

that a general catastrophe had been averted William saw to the Saxon

troops threatening his flank. Wace states that William saw the

situation on the army’s flank and led a group of horsemen down the

slope, where they isolated the Saxons and cut them down. Now, perhaps,

the fighting paused as men were allowed to catch their breath and

horses were watered in the nearby streams. William must have been

concerned at this point in the battle. It was now mid-day and his

army had achieved nothing more than a bloody stalemate. Armored

milites and groups of pedites could have briefly penetrated

the Saxon position only to be thrown back or hacked down. If victory

could not be achieved by days end the situation would look grim

indeed. The invaders were far from home with limited resources

and if the Saxons were allowed to retire they could then reorganize

and rebuild their forces. The duke needed a decisive victory before

the sun set. At this stage in the battle one of its most controversial

events occurred: the retreat of the Norman cavalry. William of

Poitiers claims the duke organized several feigned retreats as a

means of drawing the Saxons out of their position on the ridge.

Numbers of horsemen would charge the shield wall and then suddenly

retreat, supposedly in feigned flight. This action caused groups

of Saxons to charge in pursuit, at which time the Norman cavalry

would wheel around and counter-attack, thereby cutting down their

pursuers. Anti-Norman scholars stand by the opinion that these

movements were indeed genuine retreats and William of Poitiers is

simply attempting to cover up the less than stellar actions of his

countrymen. In my opinion this is incorrect and the military history

of the Normans themselves supports this position. These same tactics

were used several times by the Normans in the years preceding Hastings.

The maneuver of feigned retreat was used with success at Arques

in 1052, as well as Messina in 1060. To make the claim that Norman

cavalry was not capable of these maneuvers is to deny the history

of the people themselves. As we will later discuss, Norman military

units, either cavalry or infantry, were tightly run professional

machines. These men had trained together for years for exactly

this kind of operation so the concept of a feigned retreat is well

within the realm of possibility.

By

late in the afternoon the Saxon army still held their position on

the ridge. Their ranks had been thinned but so had those of the

invading Normans. Both men and horses in the Norman ranks would

have been reaching the limits of their endurance. William of Poitiers

relates how the duke himself had three horses killed beneath him

throughout the course of the day. Wace also provides exciting bits

of detail from this stage in the battle: how Duke William had his

helmet dented by the blow from a Saxon axe, and how Robert Fitz

Erneis managed to ride into the English lines and take the standard,

only to be cut down by the huscarls guarding it. The area around

the ridgeline would have been littered with the bodies of the dead,

causing a further hindrance to the attackers. While things seemed

desperate for the invading Normans they were equally so for King

Harold and his countrymen. Many of them had fought the Norse at

Stamford Bridge and perhaps Fulford as well. To say these brave

men were exhausted would probably be something of an understatement.

They may have been as hard as the iron protecting them but previously

fighting two major battles, as well as twice marching the length

of England to engage an invading army, was surely proving to be

too much. Both of Harold’s brothers, Gyrth and Leofwine, had now

been killed sometime during the day. As the two were surely Harold’s

main subordinates in the Saxon army the king would have no longer

had a complete sense of command and control with which to direct

his troops. According to Wace, and Henry of Huntingdon as well,

the duke now concentrated his archers upon the English position

in preparation for the final assault. The Bayuex Tapestry

indicates this by illustrating many archers in its lower band at

this stage in the battle. How organized this final assault was

is debatable. The troops would have been intermixed due to the

long duration and severity of the fighting and whether the last

attack was a coordinated affair or a general melee can only be for

the individual reader to decide. When the death of King Harold

finally came it was also the death knell for the defending Saxons.

Harold’s death has been one of the most hotly debated aspects of

the battle. The commonly held opinion is that Harold was killed

by an arrow through the eye, as supposedly depicted on the Bayeux

Tapestry. Unfortunately the tapestry has been repaired on more

than one occasion throughout its existence and the scene depicting

the king’s death is one of these areas of repair. Consequently,

the figure that seems to be grasping an arrow protruding from its

face may have originally been wielding a spear. Other theories

hypothesize that the figure being cut down to the immediate right

of this scene actually depicts Harold being slain. William of Malmesbury

concurs with the arrow theory while Wace follows along but in more

colorful detail, with the king being struck by the arrow then being

given a sword blow on the thigh while lying prostrate. The Carmen

gives Duke William the honor of breaking through the lines and

striking down his enemy personally.

Regardless

of its manner, Harold’s death signaled the battle’s end. Members

of the fyrd began to break away in retreat while the housecarls

of Harold’s personal guard chose to stand and die with their king.

By the time the sun set the battle had turned into a complete route

and the duke was forced to recall his pursuing troops due to the

falling darkness. Legend has it that William then returned to the

battlefield where he pitched his tent among the dead. The Norman

dead were recovered for burial but the Saxon slain were left where

they lay, as a carrion feast unless family members came to claim

them. Unlike most of their countrymen the bodies of Harold’s brothers

were recovered. However, the king’s body had been so badly abused

as to be unrecognizable. Because of this William sent for Harold’s

common law wife, Edith Swan-Neck, so that she could identify his

body by marks known only to her. The body was then taken to the

duke’s camp where Harold’s mother, Gytha, supposedly offered William

the body’s weight in gold for its return. William refused and

his Norman comrades joked that Harold should be buried on the shore

he had tried in vain to defend. Other sources state that William

allowed the body to be buried at Waltham Abbey in Essex and today

a plaque marks the spot of King Harold Godwinson’s supposedly final

resting place.

After

the battle William returned to his base at Hastings where he spent

several days regrouping and then moved on Dover. Enroute to Dover

he sent troops to Old Romney for retribution. Apparently two ships

from the invasion fleet had been blown ashore there and the crews

had been killed by the local militia. The duke undoubtedly dealt

with these citizens in the same ruthless fashion he had displayed

in the past. After fortifying Dover William moved on to Canterbury

where its citizens submitted. The duke then continued to take

control of the countryside around London until the city itself finally

capitulated and William, Duke of Normandy, now a conqueror rather

than a bastard, was crowned King of England on Christmas day in

Edward the Confessor’s Westminster Abbey. There were still pockets

of resistance throughout the country and the total conquest of England

was not yet complete. After the country seemed relatively secure

William returned to Normandy in 1067. He had left William FitzOzbern

and Bishop Odo in charge of the country but rebellions immediately

began to flare up after his departure. The King then returned in

1068 and marched on the rebellious city of Exter with contingents

of the Saxon Army already under his command. William continued

to deal with small cells of rebellion, as well as an invading Danish

fleet of up to 300 ships. The Danes were harassed until they withdrew

and Wiliam used the centuries old practice of Danegeld to buy them

off. Evidently even the iron-handed conqueror was not above the

realities of political expedience. In 1069 a major rebellion flared

up north of the Humber River and William marched to York. The King

now exercised his cruel will in an event that has come to be known

as the Harrying of the North in which the king adopted a scorched-earth

method of pacification. Such was the severity of the devastation

that, according to Orderic Vitalis, 100,000 people died of famine.

This figure is probably an exaggeration. However, the devastation

was great enough that the area is listed as uninhabitable in William’s

Domesday survey of 1086. By 1071 the pacification of England was

complete and the country was forever changed. The Normans introduced

new systems of government and finance to England and a new hierarchy

replaced the old Saxon witan. England was a rich country

and King William I added those resources to an already powerful

Norman realm. After the conquest of England was secure William

encountered far more contention on the continent among his Norman

subjects than he did upon the island nation. Upon his death in

1087 he left a rich and influential kingdom to his sons. In an

age where rulers were judged primarily upon their military abilities

William the Conqueror can surely be seen as one of the most capable.

While he may not be one of the most beloved kings in English history

(or not loved at all) he was certainly one of the most efficient

rulers the country has ever had.

The

battle of Hastings itself was unique for several reasons. It was

unusually long when compared to most battles of the period. You

will not find a battle that was harder fought or closer run than

the events which took place on that ridge in the English countryside

nearly a millennium past. It was also incredibly decisive, more

so than William could have probably hoped for. In one stroke he

had eliminated most of his political and military rivals and this

made the quick operations of consolidation possible. If Harold

or the other Saxon nobles had survived organized resistance who

have undoubtedly continued for quite some time, the total nature

of the victory prevented this. The Norman Conquest also took England

out of the Nordic sphere of influence and made the country a significant

player upon the European stage. One could claim that the English

empire began on the blood strewn slopes of Senlac Hill. The common

belief is that Hastings represents a clash of old and new methods

of warfare, of the giving way of infantry combat to superior cavalry

tactics. This is really a gross oversimplification of the issue.

If their methods were indeed superior why did the battle last from

nearly sunrise to sunset? At Hastings the outcome lay in doubt

right up until the last moments of the battle. This in itself does

not support the theory of total superiority in Norman arms and tactics.

If cavalry is superior why did infantry combat again rise to dominance

in the later medieval period? In reality there was little difference

in Saxon and Norman equipment. Both armies had an elite group of

professional soldiers at their core who seem to have been equipped

in nearly identical fashion, according to the Bayeux Tapestry.

Even if the Norman cavalry was a superior tactical instrument its

input wasn’t the deciding factor, as the terrain at Hastings limited

its effect. If Norman effectiveness cannot simply be attributed

to factors of equipment and tactics how were they so successful?

Can other things such as leadership, loyalty, aggression, opportunity

and even luck be factors? Some of these questions can never be

fully answered and must be left to the sands of time. However,

hopefully we can gain a better understanding of Norman success as

we discuss their military methods.

The

Norman Military Machine

|

During

the 11th century Normandy operated under the medieval

form of government known as feudalism, or enfeoffment in exchange

for obligation. Within this system a knight would be given a grant

of land in exchange for service to his overlord. In the strict

military sense, which is our focus here, the knight would be granted

a fief, or fee, in return for a specified length of military service

per year. From a military standpoint this system of government

has received far more attention than it deserves. Exactly how much

did this feudal system contribute to the Norman capability to wage

war? Were these feudal vassals the true backbone of the Norman

military machine? In his study of the knight’s fee historian J.H.

Round could only find three instances where the feudal host was

summoned to full service. The payment of scutage, or money in place

of physical service, seems to have been more common. From this

we can see that, while feudalism did indeed play an important role

in administration and government, it was not a significant factor

in Norman military operations. Like most societies during the medieval

period Normandy was a society organized for war. Most grievances

would have been resolved through military means, even if this only

meant intimidation through the physical presence of an army rather

than actual combat. A strong and capable military structure was

needed because of this ‘negotiation through force’ approach. If

the feudal host did not serve as the backbone of Norman military

operations what did?

The

true core of the Norman army was the familia regis, or kings

military household. The troops of the familia were professional

mercenary troops who were paid for full-time military service.

It must be understood that, during the 11th century,

the term ‘mercenary’ did not carry the negative baggage it does

today. The modern image of the mercenary is that of an untrustworthy

and unscrupulous killer for hire. In contrast the paid members

of the familia often showed intense loyalty towards their

lord and their lord to them. The loyalty displayed by the familia

was often far stronger than that shown to a lord by his feudal

subjects. Even when mercenary troops were not officially part of

a lord’s familia they often displayed a sense of professionalism

and loyalty far greater than their feudal counterparts. During

the siege of Bridgnorth in 1102 Robert of Belleme’s garrison was

made up of a combination of mercenary and feudal troops. Unknown

to either Robert or his mercenaries, the feudal members of the garrison

cut a deal with the besieging army and surrendered the castle, much

to the dismay of the mercenaries and surely to Robert himself.

William FitzOzbern, one of the closest confidants of William I,

was well known for bestowing lavish gifts upon the members of his

familia, in spite of incurring the king’s displeasure over

what he saw as excess. Upon his deathbed Henry I, the Conqueror’s

son, professed concern about the welfare and care of his familia

troops. Such was the bond of loyalty that one of Henry’s last

thoughts concerned these comrades in arms. The combination of money

and shared loyalty created a strong bond between a Norman lord and

his personal troops. A lord’s feudal subjects often expressed contempt

for these paid soldiers, since they saw them as inferior and of

base station. Apparently the familia often showed equal

contempt for the lord’s ‘noble’ subjects, who they saw as dishonest

and without honor. This could undoubtedly lead to friction within

an army and it would take a leader as strong as many of these Norman

lords to maintain control. To place the familia in a modern

context we may view them as the professional active-duty arm of

the Norman army, with the feudal host as a form of reserve that

would be called into service in time of greater need. The presence

of familia troops in post-conquest England doesn’t seem to

have been as great as in continental Normandy. The size of a Norman

army was limited due to issues of transport and supply, as such

the Saxon fyrd continued to supplement Norman troops in England

after 1066. A soldier of the Norman familia shared

much in common with the Saxon housecarl. The principals of service

and loyalty were much the same. Perhaps this similarity is due

to their common roots in the Nordic and Germanic areas of northern

Europe. As such, the professional soldiers of the familia

formed the truly effective arm of Norman military might.

I

have tried to avoid using the term ‘knight’ and will continue to

do so. In later centuries the scope and basis of knighthood would

change considerably, using it as a descriptor here may lead to a

false impression of who the Norman warrior really was. The Norman

soldier took two basic forms: the milite and the pedite.

In their strictest interpretations these are translated into ‘soldier’

and ‘infantry’ respectively. The term equites can be translated

into ‘cavalry’, although milite seems to have served this

definition in the broader sense. In Stephen’s reign a miles